Labor Day has lost its identity. What used to be a day that celebrated workers and their fight for shorter hours, higher pay and safer working conditions has become one that is spent rummaging through sales in big box stores where minimum wage employees are forced to work on the one day that was created to honor them.

With no commitments to action, the holiday rings hollow for many, marking only the last days of summer and a reminder that pumpkin-spiced lattes are again available for consumption. Absent are marches from Union Square to 42nd Street to pay homage to those who fought for the five-day work week or re-teachings of the Pullman Strike which led to President Grover Cleveland’s begrudging acquiescence to calls for a labor holiday in the first place. Long forgotten are the hard fought progressive wins that labor leaders like Eugene Debs and organizations like the Knights of Labor secured in the late 1800s, which begs the question, why has Labor Day become such a depoliticized holiday when its roots are so deeply entrenched in progressive politics? The answer may lie in a longstanding concerted effort to acknowledge a day of labor rather than celebrate a labor movement.

This Labor Day, like every other, will be celebrated in the opinion sections of newspapers, by politicians at podiums and by pundits on Twitter. Magically, everyone becomes a labor advocate on the first Monday of September when members of both parties dutifully acknowledge the plight of the average worker and their well-deserved day off. Not unlike the spike in people claiming Irish ancestry that materializes on St. Patrick’s Day, everyone seems to be an ardent supporter of workers on Labor Day. The fact is, the same individuals urging us to “celebrate workers” were noticeably absent during our fight for $15, the push back against Right-to-Work laws and teachers’ strikes in West Virginia, Oklahoma and Arizona. Many of them even voted to confirm Supreme Court nominees that made up the majority in the Janus decision. For many, Labor Day is nothing more than an opportunity to cover up a years’ worth of support for anti-labor policies and union busting efforts with a patronizing tweet that aims to reassure the large voting block that is working people that they actually care. The takeaway? When someone wishes you a happy Labor Day, it’s probably worth asking, “What have you done for me lately?”

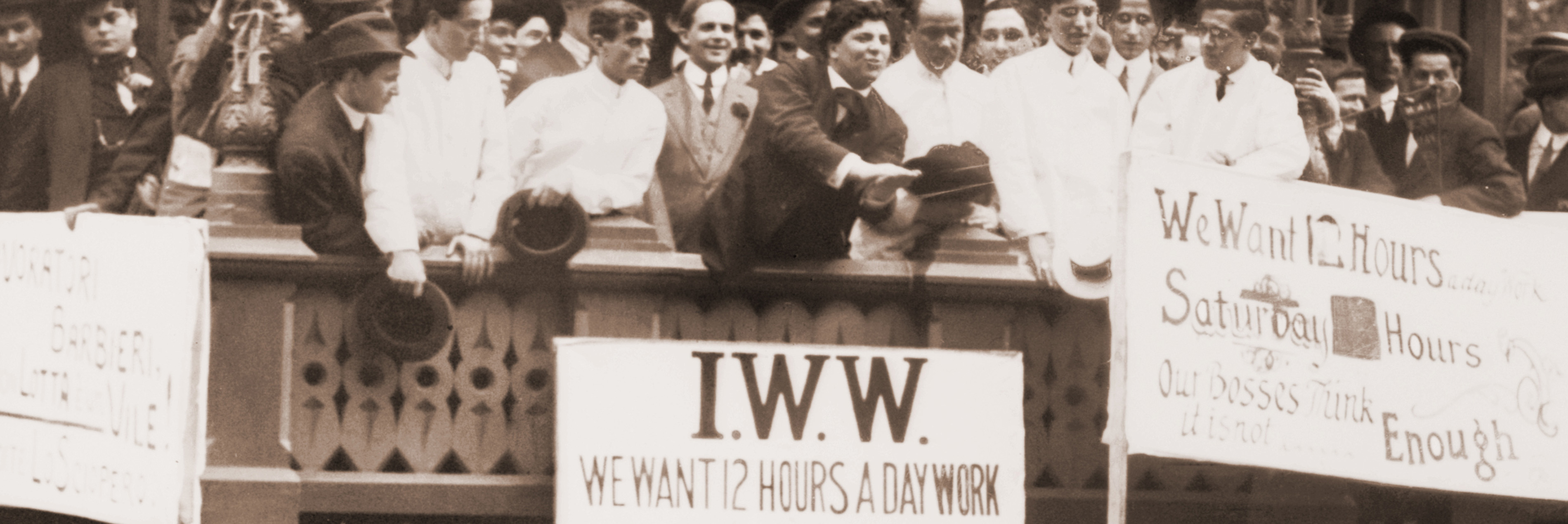

The history of Labor Day has been papered over in an attempt to diminish the importance the day has to the labor movement. According to legend, Republican President Grover Cleveland, in a charitable gesture of good faith, wielded his vast presidential powers to dedicate a day in September on which workers could enjoy the fruits of their labors. This watering down of history does a great disservice to the late nineteenth century Labor Movement and attempts to co-op a story that rightfully belongs to workers. Contrary to popular belief, Labor Day was born long before President Cleveland made any declarations. On September 5, 1882 thousands of workers took to the streets in New York City to advocate for an eight hour work day, protest poor working conditions and demand a labor holiday. The movement began to grow as cities, and eventually five states, recognized what eventually became known as “Labor Day.” The notion that Labor Day was “given” to workers is a falsehood. Activists all over the country earned Labor Day and, culminating with the end of the Pullman Strike in 1884, imposed enough political pressure on Grover Cleveland to oblige him to grant it to workers as a federal holiday.

The battles that gave birth to Labor Day were fought long ago, but many of the same issues remain. The rise of smartphones and tablets have us constantly connected to our work and has effectively nullified the eight-hour work day; the federal minimum wage has failed to keep up with inflation leaving men and women with full-time jobs poverty stricken; and, in many industries, employers refuse to maintain reasonable standards of safety leading to on-the-job injuries and deaths.

These are not issues that can be resolved by celebrating labor once a year in the form of tweets, speeches and op-eds. These are battles that must be fought year-round, and bolstered by a nuanced understanding of where the Labor Movement has come from and where it is going. To appropriately celebrate Labor Day we should honor its true meaning, remembering those who paved the way for its creation and passing down the lessons learned from Labor Days past. Perhaps most importantly, it should be a day of action where we look to the future in order to honor the past. That means joining a picket line, writing to your elected officials and canvassing for labor friendly candidates. So this Labor Day, let’s celebrate the true origins of the Labor Movement and take a hard look at the work that still needs to be done—we may find that deep in the origins of this holiday hides the key to renewing and reinvigorating a Labor Movement worth celebrating.

Mobile Image

Mobile Image

Mobile Image

Mobile Image

Mobile Image

Mobile Image